2024 JUGADOR COMO PELOTA, PELOTA COMO CANCHA

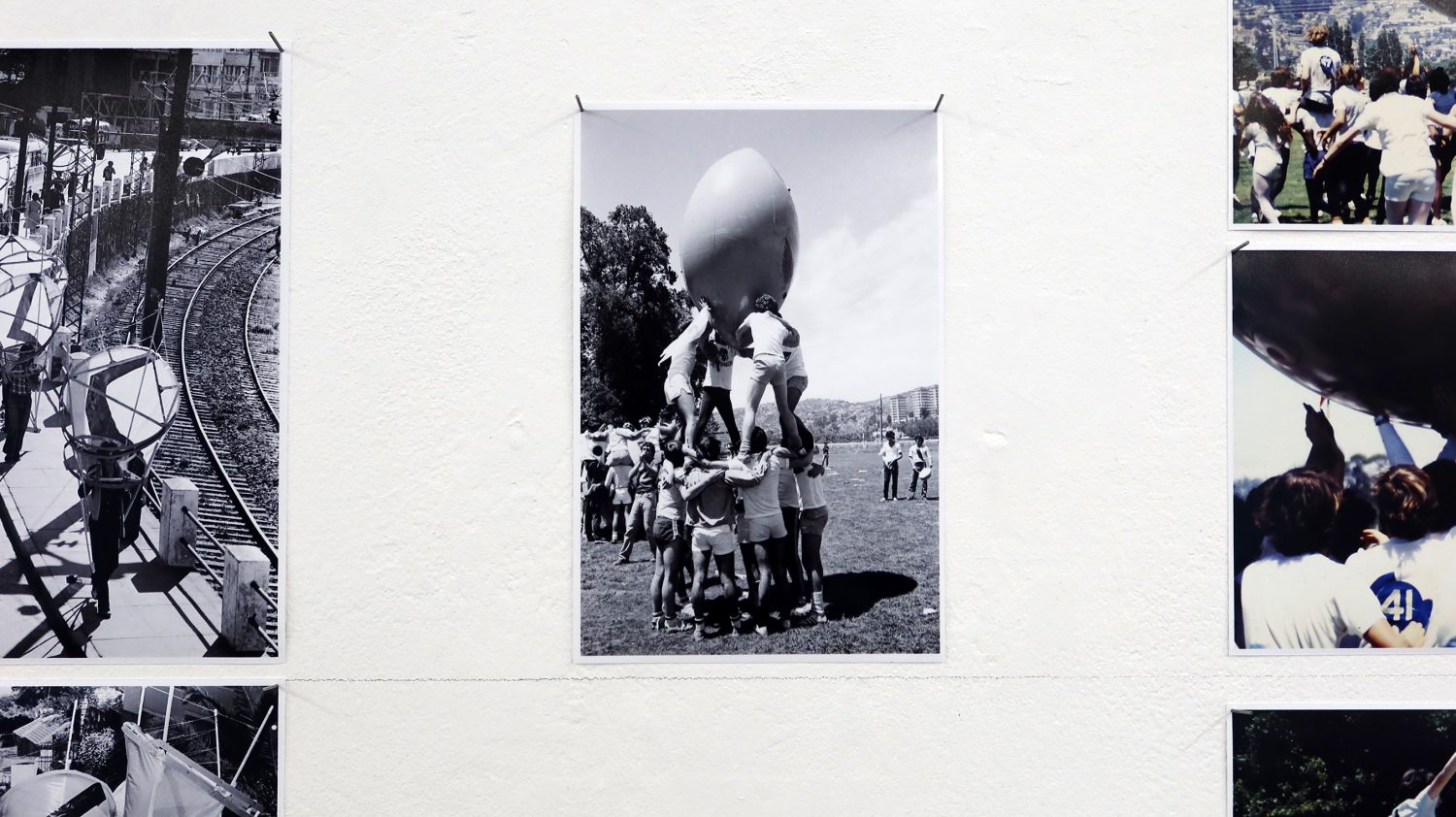

Installation views, Jugador como pelota, pelota como cancha [The Player as Ball, The Ball as Field]

Exhibition about Torneos by Manuel Casanueva, organized by Skinny Dipping

Zsenne Art Lab, Brussels, Belgium

November 20 – 24, 2024

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

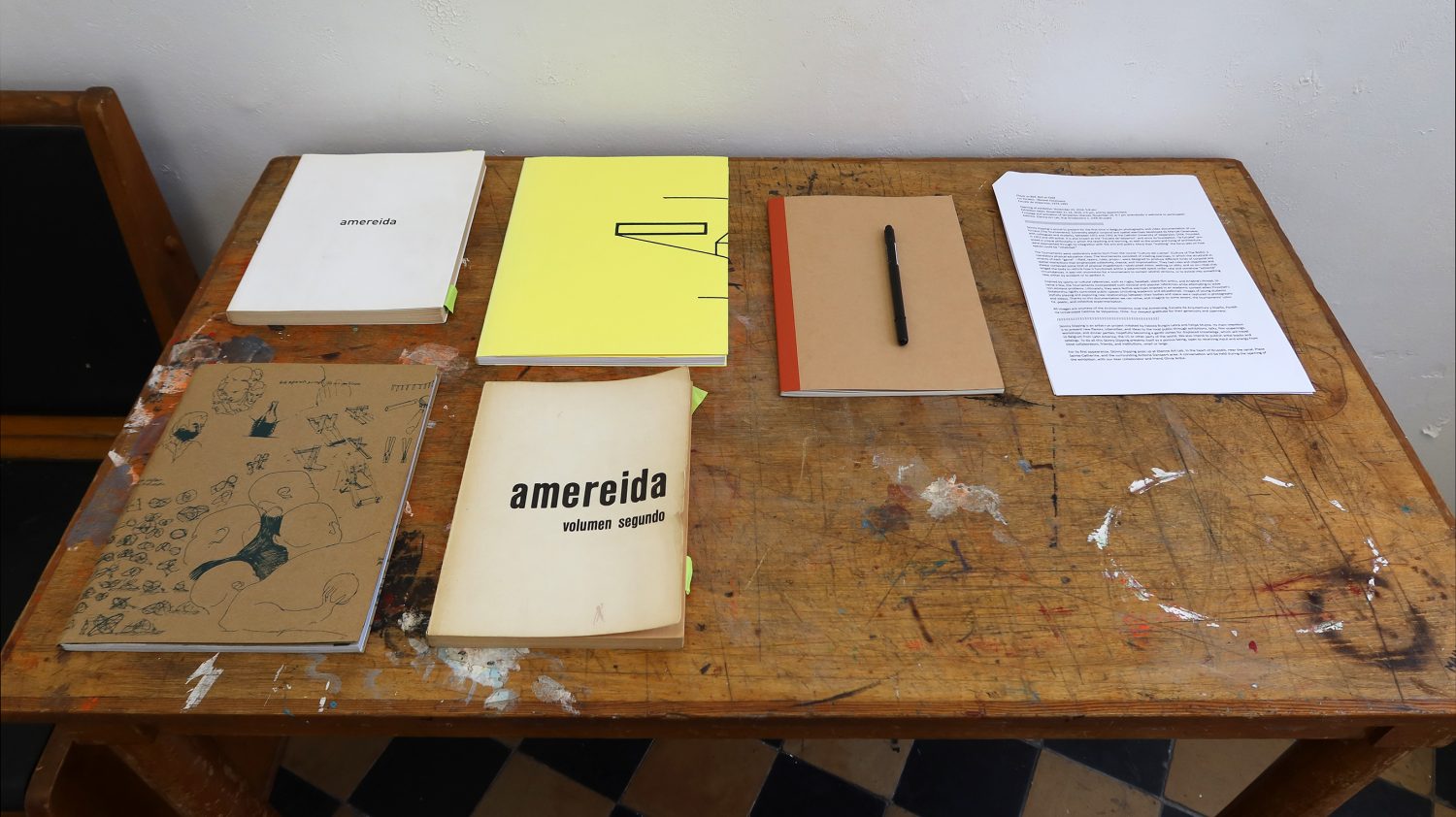

Press release: Skinny Dipping is proud to present for the first time in Belgium photographic and video documentation of Los Torneos (The Tournaments): Extremely playful corporal and spatial exercises developed by Manuel Casanueva, with colleagues and students, between 1974 and 1992 at the Catholic University of Valparaíso, Chile. Founded in 1952 and still active, it is also known as the “Escuela de Valparíso”, and since its foundation, “la Escuela” proposed a unique philosophy in which the teaching and learning, as well as the praxis and living of architecture, were approached through its integration with the arts and poetry. More than “building” the focus was on how spaces could be “inhabited.”

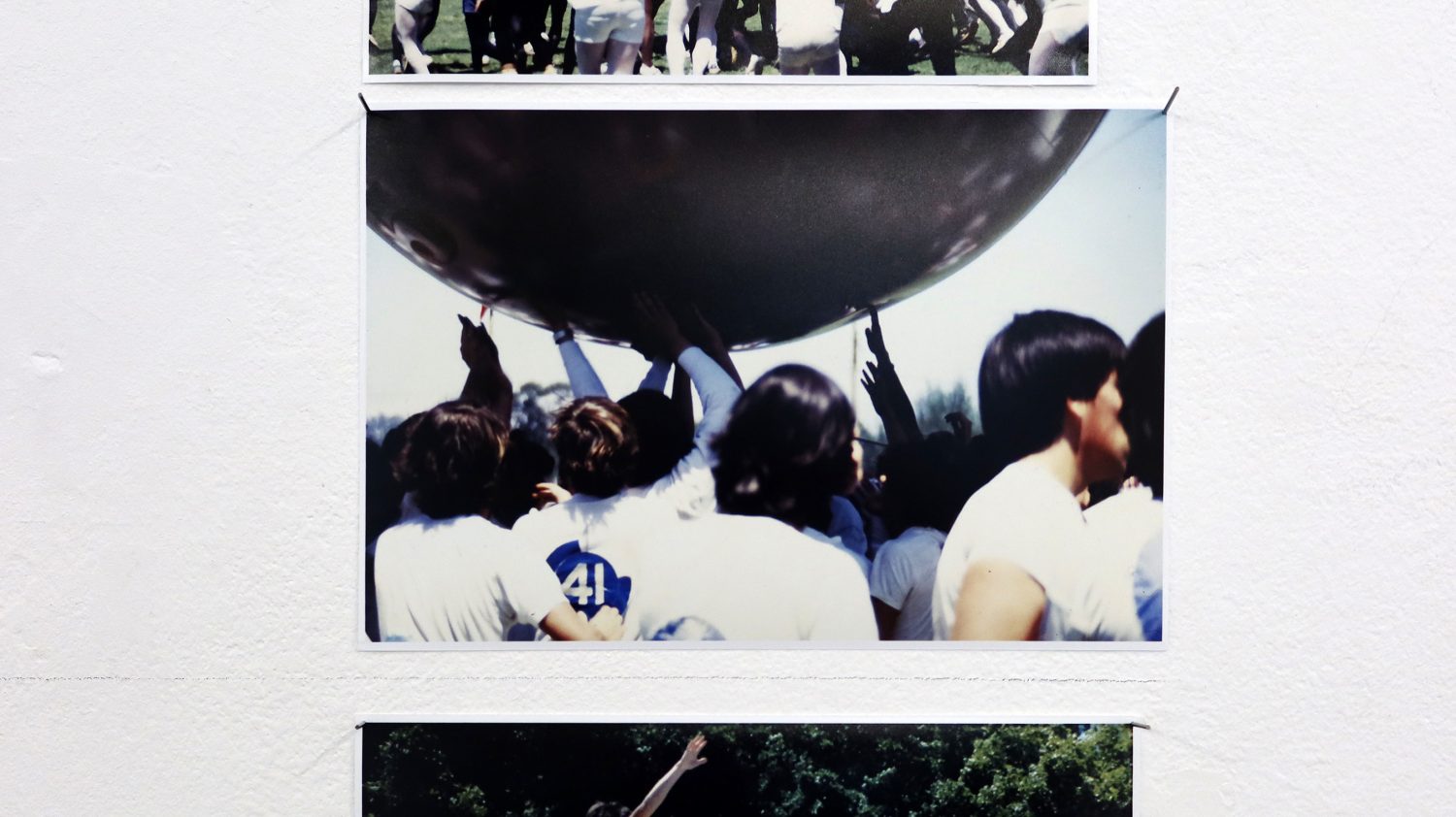

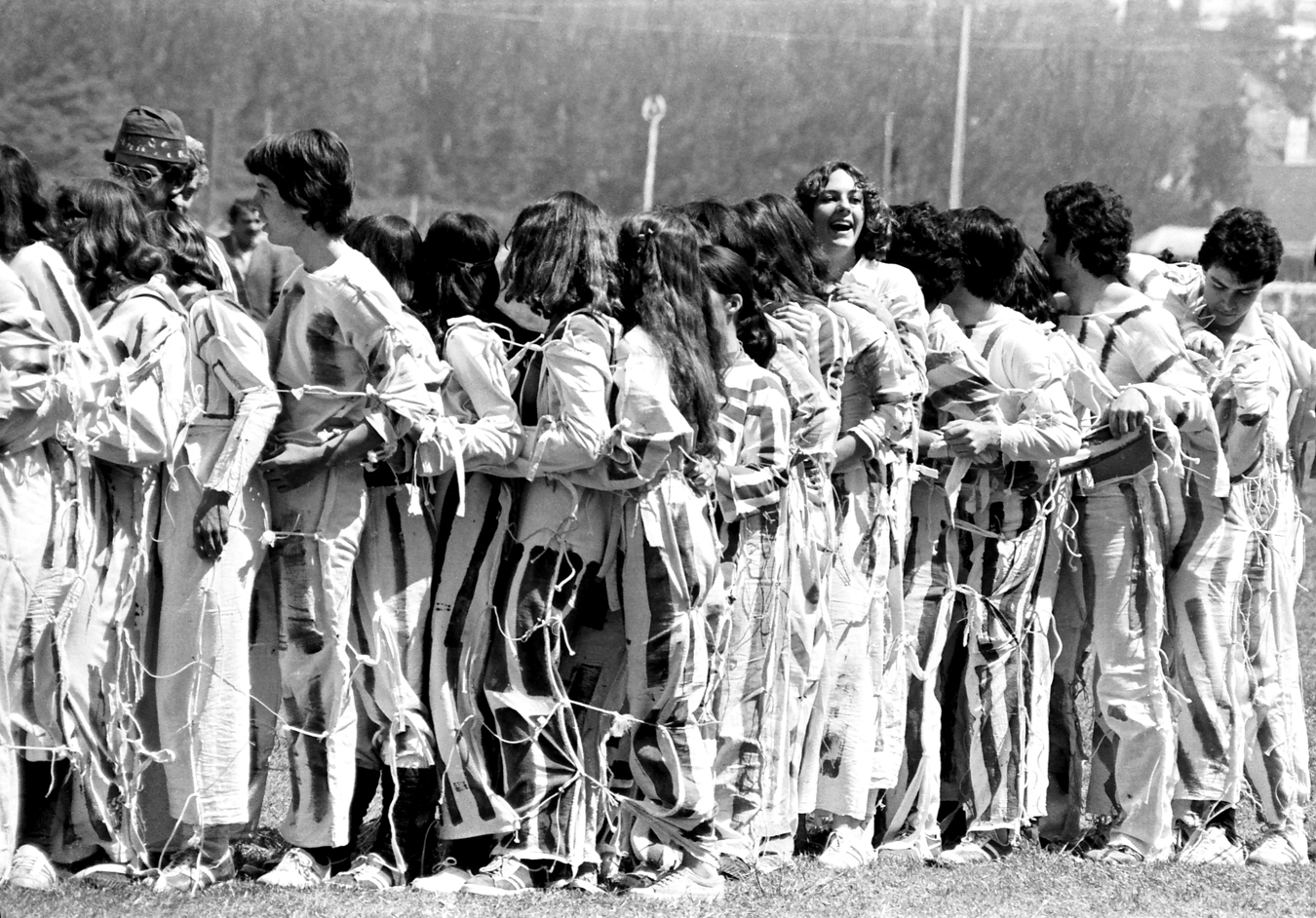

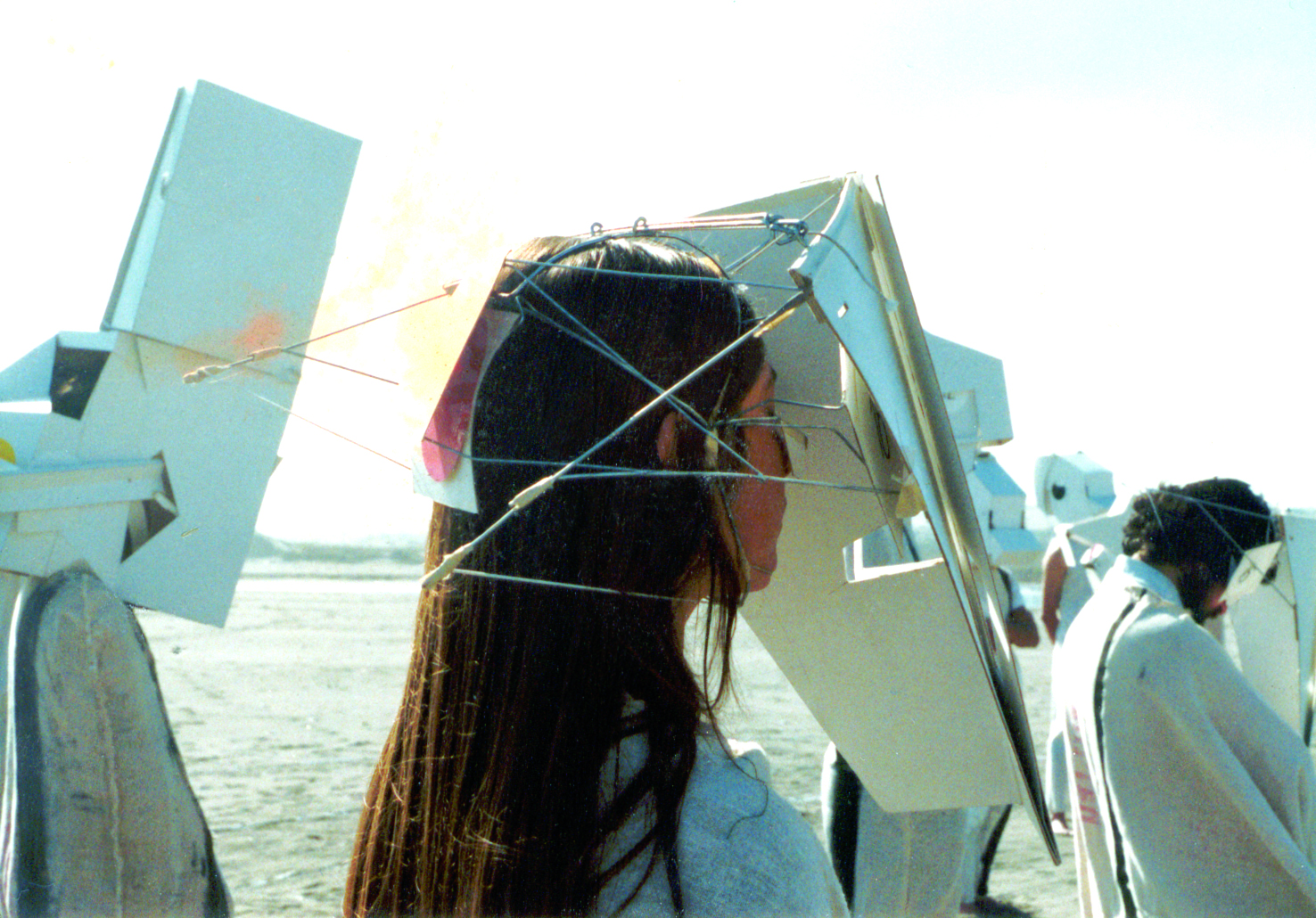

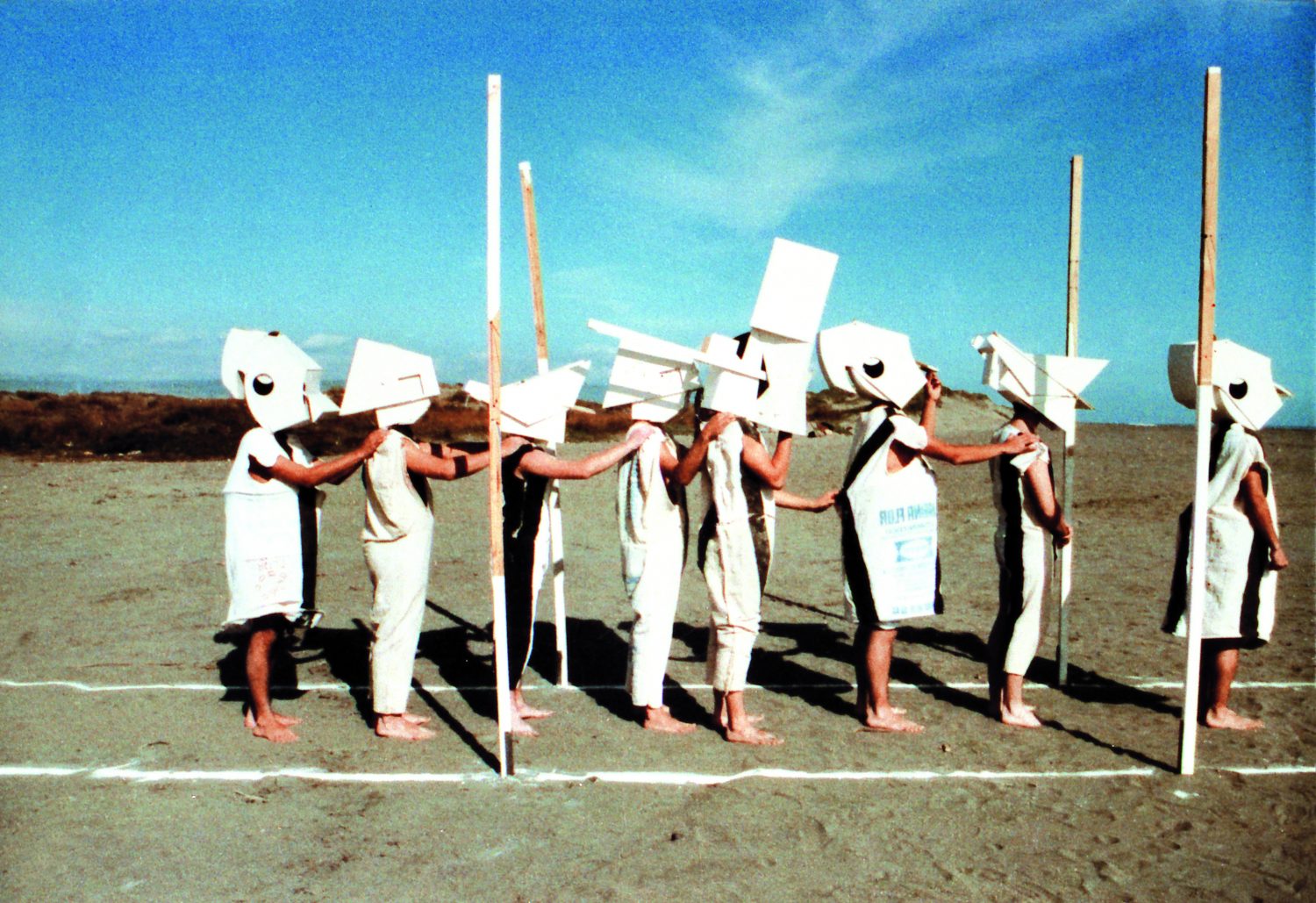

The Tournaments were celebratory events born from the course “Cultura del cuerpo” (Culture of The Body), a mandatory physical education class. The tournaments consisted of creating exercises, in which the structural elements of each “game” —field, teams, rules, props— were designed to produce different kinds of corporal and spatial interactions that emphasized collectivity, chance, and improvisation. They had rules and objectives and always contained some kind of physical impediment—obstructed vision, walking on stilts, and so on—that challenged the body to rethink how it functioned within a determined space under new and somehow “extreme” circumstances. It was not uncommon for a tournament to contain several versions, or to evolve into something new, either by accident or to perfect it.

Inspired by sports or cultural references, such as rugby, baseball, silent film antics, and Ariadne’s thread, to name a few, the Tournaments incorporated such classical and popular references while attempting to solve non-existent problems. Ultimately, they were festive exercises enacted in an academic context when Pinochet’s dictatorship rigidly controlled public spaces (including academic and educational). Images of young students joyfully playing and exploring new relationships between their bodies and space were captured in photographs and videos. Thanks to this documentation we can relive, and imagine to some extent, the tournaments’ colorful, poetic, and collective experimentation.

All images are courtesy of Archivo Histórico José Vial Armstrong, Escuela de Arquitectura y Diseño, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile. Our deepest gratitude for their generosity and openness.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]

Skinny Dipping is a Brussels-based artist-run project initiated by Fabiola Burgos Labra and Felipe Mujica. Its main intention is to present new flavors, intensities, and ideas to the local public through exhibitions, talks, film screenings, workshops, and dinner parties, hopefully becoming a gentil vortex for displaced knowledge, which will travel to Belgium from Latin America, the US or other parts of the world. We also intend to publish artist books and catalogs. To do all this Skinny Dipping presents itself as a porous being, open to receiving input and energy from close collaborators, friends, and institutions, small or large.

For its first appearance, Skinny Dipping pops up at ZSenne Art Lab, in the heart of Brussels, near the canal, Place Sainte-Catherine, and the surrounding Antoine Dansaert area. A tour/conversation will be held during the opening of the exhibition, with our dear collaborator and friend Olivia Ardui.

Opening of exhibition: November 20, 2024, 5-8 pm / Dates: November 19-24, 2024, 2-6 pm, and by appointment / Finissage and activation of Serpientes (Danza): November 24, 4-6 pm / Address: ZSenne Art Lab, Rue Anneessens 2, 1000 Bruxelles

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Lost in Concón

In January 2012, I was in Chile for an exhibition at Casa E in Valparaíso. By chance, my friend Maria, who also lives abroad, was there too. While chatting one night at a party, we decided to travel together to visit the archive of La Escuela de Valparaíso. I had to return for a talk, and Maria had promised a visit to Don Adolfo, the person in charge of the archive, where she had spent about two years researching and had built a beautiful work friendship. The visit was a huge discovery for me, as I knew very little about the school’s history. It was an eye-opening experience as I met people who worked there – even though it was mostly through formal introductions – but above all, I was able to look at precious documentation ranging from the 1950s to the 1980s. What I saw seemed immediately radical, in its mixture of spatial and poetic exploration, yet mostly as an ongoing pedagogical experiment.

Two records, “Taller de Arquitectura” and “Curso del Espacio” (both circa 1958), were humble foldable sheets of paper with black and white photographs attached. Next to them were descriptive texts of the exercises. The simplest – and in my opinion, the most beautiful – consignment I saw that day consisted of a small photograph of a house in Valparaíso. Next to it was a larger photo that provided a general view of a hill in the city. Accompanying both photos was this text: “Photographs #5. Valparaíso Houses. The small photo is the same one given to each student with the mission to find that house in the hills of Valparaíso. The other photo is an example of the structure of these hills. Class by Professor J. Vial.” The exercise required the students to wander through the many hills until they found the house. It involved getting lost, not knowing what to do or where to go, yet having an objective. Finally, Don Adolfo gave us a warm goodbye, a big smile on his face, and a generous invitation to return, hopefully soon.

The second part of our exploration involved visiting Manuel Casanueva, a retired professor at the school and creator of Los Torneos, at his house in Concón. Again, I hardly knew anything about him or his work, aside from some images I had just seen in the archive. Although the trip was supposed to be short—about half an hour by car—and María insisted she knew the way, we got lost. We drove around town and its outskirts for about an hour or more, trying to locate a street and a house but struggling to distinguish between one dirt road and another. Like many coastal towns in Chile, Concón is a precious mix of countryside and coast. Surrounded by forests and nestled between hills, it lacked clear urban signage— with the sound of the ocean in the distance— making it easy to lose our sense of direction. Our journey was filled with laughter and a gloomy feeling about being late to arrive at Manuel’s house, but we finally made it.

I sensed that Manuel received us with a mix of happiness and suspicion. He was happy to see María again, but I think he was also skeptical about my presence; he had a “who is this intruder?” kind of look. María had warned me about Manuel’s advanced age, especially since he suffered from Parkinson’s disease. Seeing him walk hunched over was surprising because he radiated a lot of energy. While it may be a cliché, I got the impression that he possessed a strong internal force that was in a constant battle with his body, fighting against his limitations.

Later, sitting in his studio, we were able to chat in a relaxed setting. I felt incredibly lucky to see a good number of medium-format color photographs of several Torneos organized by him, fellow professors, and students. We drank tea and chatted more, although the conversation largely flowed between him and María, leaving me feeling like the stranger in the room. He fondly recalled the costumes and artifacts used in each Torneo, cherishing memories of those events. At the end, he showed us his most recent work, which consisted of small and medium-sized watercolors. These were simple and humble compared to everything displayed in the Torneos, yet they were also full of color, formal clashes, and energy, reflecting a person who could not remain still.

His house was very simple—representing middle-class coastal Modernism—with low ceilings and brick walls. It featured an interior garden and a hallway with large floor-to-ceiling windows. Outside was a glass table topped with a metal abstract sculpture. The table was surrounded by four chairs, seemingly arranged to either view the sculpture or to provide a spot for someone to sit and admire it. I later learned that the piece was a gift from Claudio Girola, a friend and colleague at the school. After a couple of hours, we finally left. Nonetheless, the images of these young people enjoying themselves, playing, and exploring their bodies and interconnectivity remained etched in my mind, formal and festive experimentation, colorful and poetic… How to learn more from this? Why is this so unknown? Why aren’t we taught this at art school? Is there any relationship with the Brazilian artists of the same period? (mostly thinking in Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Helio Oiticica) How did this happen in a school of architecture?

I left with these questions, and furthermore with the deep conviction that I had to do something, I had to “spread the word”. For a moment, remembering getting lost on the way to Manuel’s home, I felt like that student in the 1950s’, looking for the random house in Valparaíso, yet comfortably seated in a car.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

….